This week has taken us from the lowlands of Lancashire to the heights of the county, and we have now begun descending into Yorkshire. We’ve been blown about, soaked to the skin, dried, drenched again and bathed in sunshine! En route we have become entwined with England’s industrial past, it’s rise, decay, regeneration and resurgence in new ways. We’ve discovered stories of the workers behind our history, those who toiled in the inhumane and often deadly conditions of England’s dark satanic mills.

Cotton is the thread winding through the history of the Leeds Liverpool Canal. The longest canal in England travels 127.25 miles between the inland wool town of Leeds, to the coastal sea port of Liverpool, crossing the Pennines along the way. Work on the canal started in 1770. It was built in a number of sections and was finally completed in 1816.

Barges would ply their trade from Liverpool where they had been laden with huge bales of cotton shipped from America. The cotton would be unloaded at wharves along the way, and from there redistributed to local cotton mills.

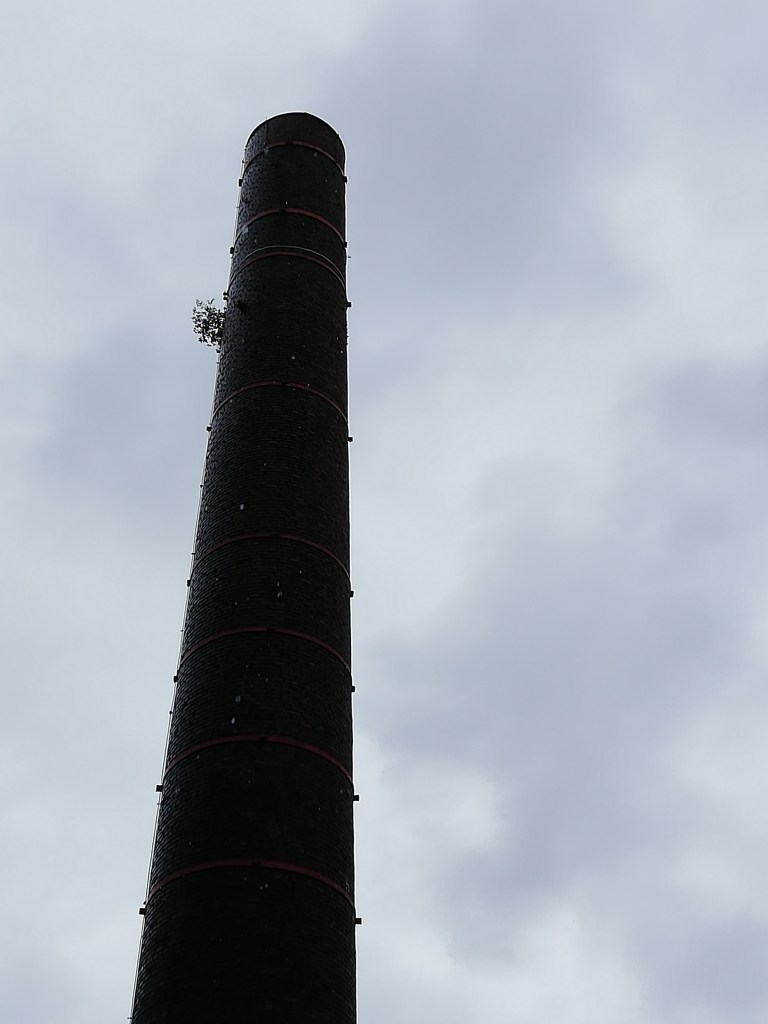

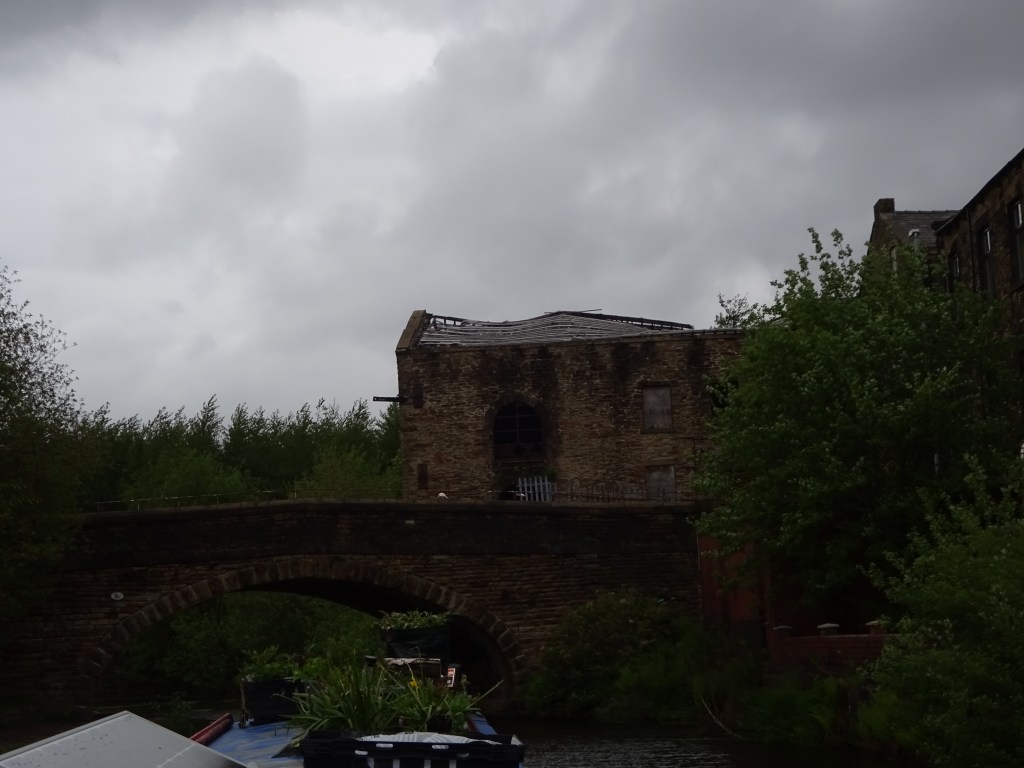

In Chorley what was Canal Mill still stands imposingly at Botany Bay. In its heyday as a cotton mill, men worked on the top floor as spinners and women were employed on the lower floor as creelers, getting the bobbins ready for the spinners. It last spun cotton in the 1950s and currently stands empty after failed attempts to turn it into a shopping and leisure destination.

The Imperial Mill at Blackburn also looks forlorn. It was built on the banks of the canal in 1901 and was in production until 1980.

Blackburn itself was known as cottontown through the 18th and 19th century and was famed as one of the most important cotton producers in the world. From the windows and architecture of houses it’s possible to see the origins of the cottage industry. Space and light was created for handlooms in terraces, or in loomshops attached to the backs, the sides or in the cellars of their homes. Once the Industrial Revolution brought mechanised looms housed in specially constructed factories, the landscape changed again.

The canal was fundamental to the development and functioning of the spinning and weaving mills, as well as the associated industries of paper mills, collieries, breweries and brickworks that flourished in the region.

The collieries have had a major impact on some areas of the canal – subsidence has led to significant work needing to be done to maintain the working of lock flights, and in some places the canal is now much lower than it was as we can see from high sides!

The architecture alongside the canal has in some cases been repurposed, recycled if you will. Apartments, houses, offices, restaurants and cafes have sprung from wharves and mills.

Many though remain untouched by humans, if not the ubiquitous Canada geese, waiting for funds and entepreneurs to revitalise them.

The structure of the canal remains unchanged, running like a ribbon through the urban and rural landscape. It rises through the Lancashire mill towns, skirting the edges of most but in one former mill town it runs spectacularly 60ft above the town centre on The Burnley Embankment. The Embankment was an engineered solution to keep locks at a minimum because they took time to navigate (as we know!). Regarded as one of the original “seven wonders” of the British Waterways the “Straight Mile” as it’s known locally gives good views of the rows of traditional terraced houses with their symmetrical chimney stacks…even in torrential rain!

Out of Blackburn the countryside opened up, the sky expanded and we began to encounter the M65, as it crossed and recrossed the canal. Lorries and cars hurtled along, oblivious to us and our world of 4mph, geese, swans, sheep and moors rolling to the waterside.

Spectacular views were laid out for us all to see even through the rain. For us fortunately they didn’t pass in a blur or the stress of a rush but we were able to appreciate them, to marvel and enjoy.

Just before Burnley at the Pilkington Bridge is a small, blue plaque. It remembers and reminds us all of an explosion at the nearby Moorfield Pit which killed 68 men and boys and seriously injured 39 on the morning of 7 November 1883.

It was a deadly gas explosion which led to safety recommendations that affected coal mines across the country, including replacing the traditional Davy Lamp. The youngest to die in the disaster were just 10 years old, James Atherton and Aaron Riding.

The collieries, the mills and the canals were dangerous places for children in those days – many worked with their families on the commercial barges, barges like Kennet. A short boat, built to the exact dimensions to allow her to fit in all the locks of the Leeds Liverpool , Kennet travelled the whole Leeds Liverpool canal carrying cargo. Now on the National Register of Historic Vessels, we came across her not far from her permanent mooring at Greenberfield Top Lock preparing for filming series 2 of the latest All Creatures Great and Small.

Not only historic barges are taking on a new life – bringing authenticity to period dramas, but narrowboats too are transforming their purpose. At Accrington we came across Small Bells Ring, a recreational/research vehicle (RV) Furor Scribendi, which has been built as a floating library of short stories. It transports them across the canals, and lets the words of those stories transport their readers to new places, just as the canal takes us to new places, new views, new discoveries dozens of times every day. The boat is travelling through Lancashire inviting families and individuals to explore new worlds through the written word, and will be in Coventry as part of the City of Culture events in July.

We’ve spent the week traveling slowly, thoughtfully, from Greater Manchester, through Lancashire to Yorkshire. It’s been a week of sensory overload – spectacular scenery, everything sodden and shimmering in the rain, sudden moments of joyful sunshine, which set everything sparkling in a different way. History grounded within the scenery, stories of people and places. Far reaching views of rolling hills have contrasted starkly with crumbling stonework in urban sprawls of old mills that once hummed with industry. Ducks, geese and moorhens living in urban detritus of rubbish contrasted starkly with the exhilarating freedom of curlew with their gangly legs and distinctive curved beaks, flying with the rolling motion of a wave through clear skies over open fields.

William Blake captured England with all its contrasts, in his recognition of England’s pleasant pastures green, dark satanic mills and unfolding clouds. We’ve seen them all this week in a head-turning, never-ending slideshow of sights that have underlined for me how much there is to see and explore in this country.

Seeing this diverse countryside at a slow pace allows us to appreciate it, to experience it in a way you can’t whizzing through at speed. We have chosen to travel the ‘Super High Way, Super Wet Way, Super Low Way, Super Slow Way’, in what I would add is the Super Best Way.

It’s been a memorable week – 62 miles and a quarter of a furlong on the Leeds Liverpool Canal through 57 locks and 2 tunnels taking us from Wigan to Skipton.