The Covid pandemic has changed many things, the ways we work, relate to each other, behave and also our language. Pandemic, social distancing, furlough, epidemiology and lockdown have become familiar to us, many have been ones we’ve used daily.

Here on the canals locks are also something we use daily, an essential to travel. In the days since April 12 when the last full lockdown lifted, we have travelled 254 miles and needed 230 locks to do that. Locks take the boat up and down the contours of the land. Essentially they are chambers with gates at either end. The boat comes in one level and the gates behind it are shut. Operating openings (paddles) in the gates ahead of the boat the water in the lock (and the boat) is either lowered or raised depending on which way you are travelling.

Once the water in the lock is the same as the water in the canal for the direction of travel, the gates open easily and the boat glides out on a new level. Sounds simple? The engineering principle is straightforward. Sometimes the mechanisms are tough going, the gates heavy and difficult to move, but the system works.

The simple but incredibly efficient lock mechanism on canals is our only way of climbing and descending hills with boats. Locks have taken us over the Pennines once on this trip and are currently taking us back across their splendour.

Since the pandemic hit the word it seems the word lock has moved from being instantly associated with security, safety and protection to constraint (lockdown). Locks on canals are both constraint and protection but if not treated with respect they can be dangerous and indeed deadly. Talking of such dire things, we survived the Guillotine Lock on the Huddersfield Narrow – it was an engineering solution to a lack of space at restoration and works beautifully although the low bridge before it nearly took my head off!

Rising in a lock is literally uplifting, particularly in the narrow locks which only take a single boat at a time, but the principle is the same in wide locks, or multiple, staircase locks.

You take the boat in at a low level into a dark dank chamber made of substantial hewn stone blocks, often with water and mud dripping from the sides. You can only see the top of the lock by craning your neck, and on a sunny day it feels like any warmth has been instantly obliterated. Sometimes there are plants clinging in the cracks of the stones, ferns, buddleia and occasionally the all-invading Himalayan Balsam. If I see the latter and can reach it safely, I yank it out to put it where it can dry out and die, to support our native species.

Down in the depths it feels joyous to be propelled up into the sunshine, by the rising waters swirling underneath as the paddles open. Every time the greenery , and the warmth after the darkness seems more vibrant, more alive. Taking a boat such as ours through 74 locks on the 20 mile Huddersfield Narrow Canal is made easier because she’s only 50ft long and the locks are 70ft long.

That length gives space for whoever’s at the tiller to move the boat well back from water flowing in ahead of the bow (which could swamp the boat), and it’s easier to make sure the fender and front of the boat doesn’t snag on the end gates which could result in the boat tipping and sinking. The narrowness of 6ft 10inches just fits the boat snugly giving a feeling of protection, as long as we’ve made sure all fenders that protect the sides are up – so they don’t snag and jam the boat in the lock.

Going down is a different matter. You enter in the the light, and gradually plunge down into the darkness of lower levels until the lower level is reached and the gates open to let you out. It’s vital as you descend that you keep the boat forwards of the stone or concrete cill which the gates rest on, and which holds back the water of the pound (the area of water between locks) that you are leaving. Getting the back of the boat caught on the cill can sink the boat. Letting concentration slip whether on the tiller or the lock can be costly.

So locks on canals combine protection, constraint and danger. On the Huddersfield Narrow there’s been the added concern of water levels – we’ve been aground several times travelling between locks because it’s been so shallow, and struggled to moor in many places we fancied because of the depth. Employing reverse gear and our trusty bow thruster (me and a big wooden pole – we don’t have modern gismos), we’ve carried on until we’ve found somewhere suitable… although one night we did look more like we’d abandoned the boat after a bout of careless or drunken driving rather than neatly moored up! It was the only way to moor, and the dog managed to get off the bow (front), even if he (or we) couldn’t reach the bank from the stern (back).

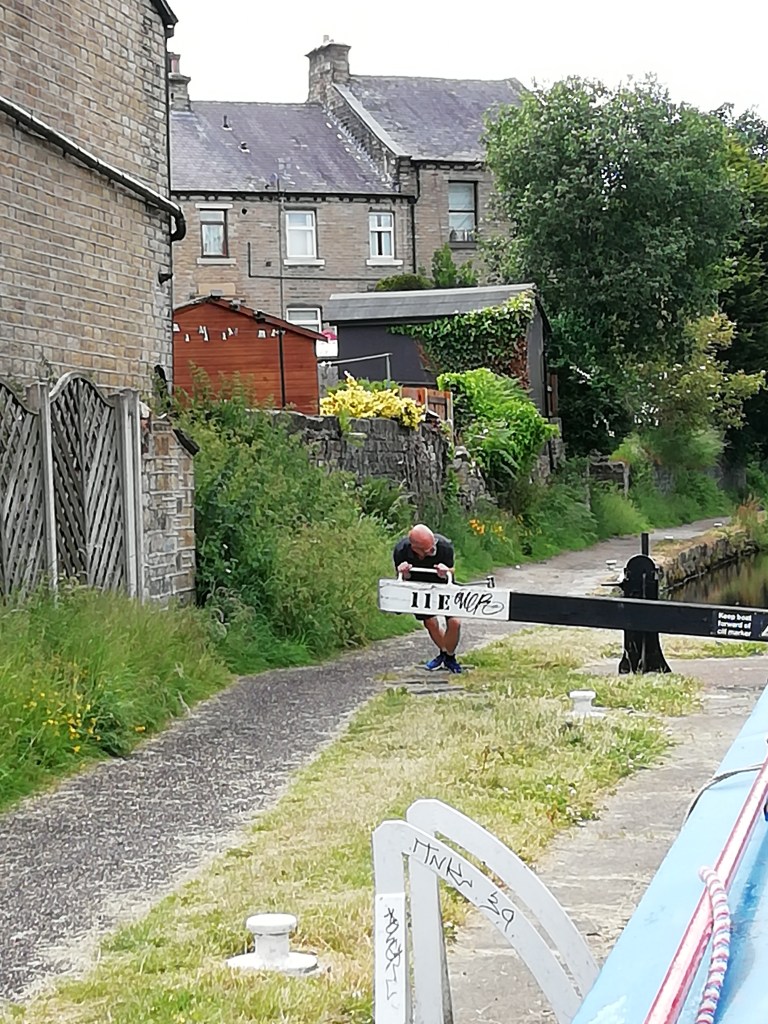

It’s been different for me on the Huddersfield Narrow, because I’ve taken the tiller after the first few locks, and Steve has been lockwheeler armed with a windlass and handcuff key.

With the dog peacefully sleeping at my feet comfortingly unaware of my incompetence, I got over my hesitation at steering the boat through the hurdles of pounds, locks, bridges and mooring. It’s all too easy to leave it to the more experienced one aboard, but that way I shall never learn. As with anything I need experience in different situations, on different canals to build confidence, skills and knowledge.

Each pound and each lock is different, and although I am trying not to make this a contact sport as some hire boats do, I have had some minor bumps too but with no resulting damage to structures or the boat! Knocks tend to occur when trying to fit the boat into a tight channel.

It’s been a privilege to see the canal from another perspective. Work on the narrow canal from Huddersfield to the Ashton-under-Lyne near Manchester began in 1794. Five years later coal and textiles were being transported along it’s length although they had to be loaded on and off barges onto horses and carts to cross the Pennine Hills at its summit. In 1811 construction of the legendary Standedge Tunnel was complete and the entire canal was navigable for commercial vessels. The tunnel remains the highest above sea level, longest (5000m, just over 3 miles) and deepest (190m) tunnel in the UK began being constructed in 1794.

The Huddersfield Narrow operated for 140 years commercially. It was officially abandoned in 1944 although some stretches were still used for local traffic until the 1960s. It then fell into disrepair and much of its length became derelict. Campaigners fought from 1974 to bring it back into use and it was officially reopened in 2001. No commercial traffic uses it now, but for leisure boats it provides a unique route through the Pennines. Ongoing restoration continues and even Blue Peter was involved in 2015.

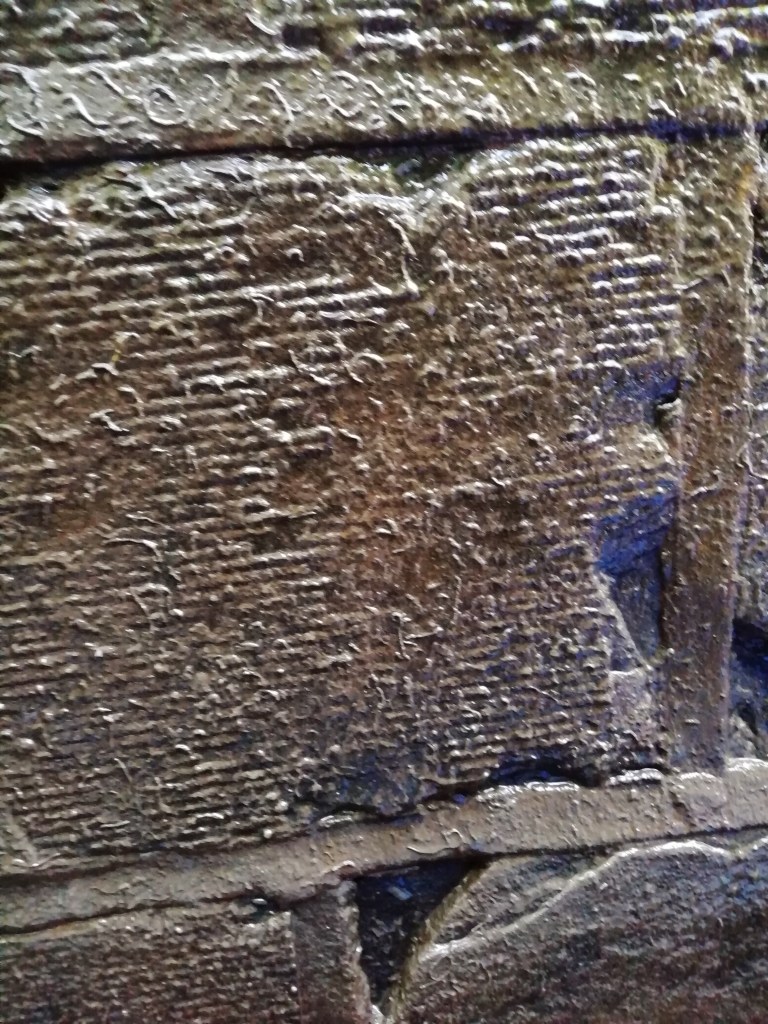

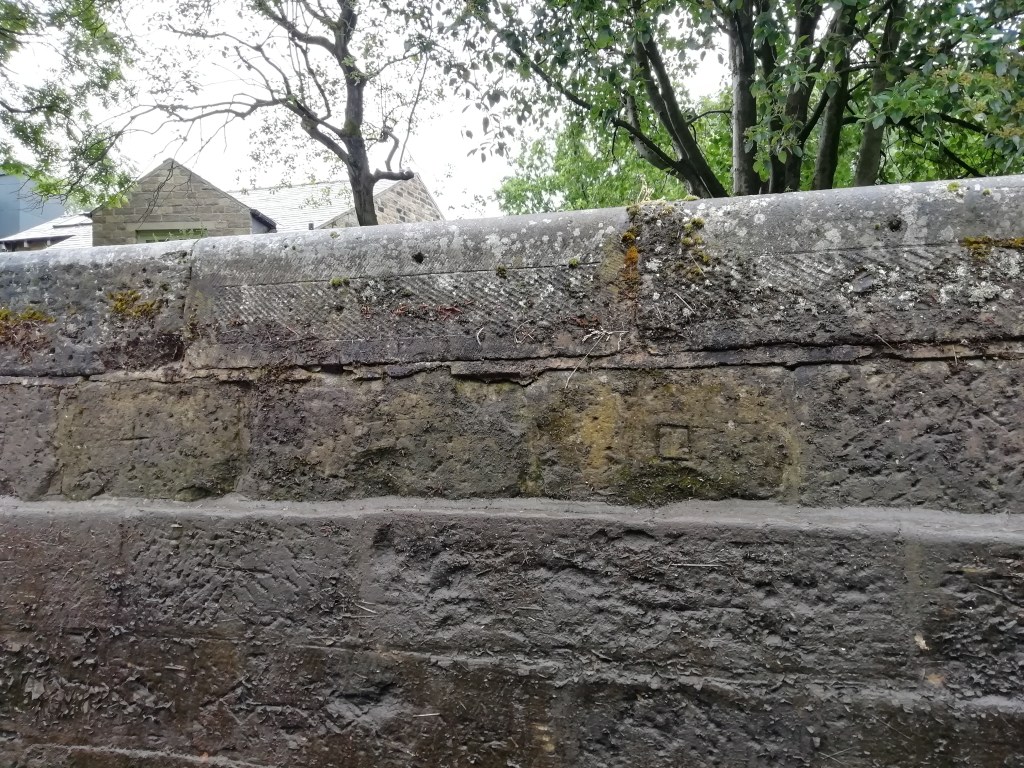

The locks themselves are a unique connection with not only the original workmen (navvies as they were called) who built the canal, the commercial barges who plied this route, but also to all those in more modern times who worked so hard to get the canal reopened. As you hold the boat steady in the locks, waiting for the waters to lift you up or carry you down, the very stones around you are marked with the passage of time. Some bear the scars of less than careful boatmanship, others the heritage of their origins, and some more intricate symbols.

Carved with shapes, and sometimes initials, perhaps from original lock makers, bored tillermen or modern day makers, the stones bear a patina of mud and water that makes their individual markings glisten. Some marks are repeated at intervals, as if indicating certain stones form a pattern. What the marks actually mean, or who the makers expected to see them would be fascinating to know.

These huge lock stones give a sense of permanence and protection from the surrounding earth, but if a boat capsizes in a lock with the force of the swirling water currents, those self-same stones would constrain, even imprison the boat and its inhabitants.

Taken carefully and with respect, the lock is a secure, safe way to traverse the hills and dales of England, a way unchanged over centuries. The Huddersfield Narrow has glorious carried us through the permanence of agricultural fields and past mills, some of which are still working, others have been converted like Titanic Mill. Completed the year the famous boat was launched (and sank), it now houses luxury apartments and a spa.

This narrow canal has carried us through vibrant villages, past houses old and new, and it now carves its way with pride through the heart of communities which welcome it and those it brings. These pictures are from the Yorkshire village of Slaithwaite apparently prounounced Sla-wit, delightfully down to earth and buzzing. Where it says Bank, that’s just what you find – they say it as it is in Yorkshire tha’ knows!

We’re booked to travel through the Standedge Tunnel early next week, and will see for ourselves its hewn interior. We don’t fortunately have to leg the boat through – pushing the boat through with our legs on the sides as was the way in days gone by, although I am sure after all this time at the tiller my legs could do with the exercise.

Leaving the tunnel we will start on one of the fastest, and most consistent periods of travel we’ve undertaken. We won’t be on a slow route despite remaining on the canals – The slow machine that England was...

No leisurely days for us in the coming weeks but hopefully we can make it on schedule – 132 miles, 112 locks and another 5 tunnels will bring us back to the Leicestershire village on the River Soar that we left 10 months ago. We shall see family, friends and take part in annual village celebrations before moving our home on again.

I hope the experience of long days travelling the waterways may bring a little understanding of the canals as those on working boats saw them – routes through the incredibly diverse countryside of England. We are, after all travelling in their shadowy wake.